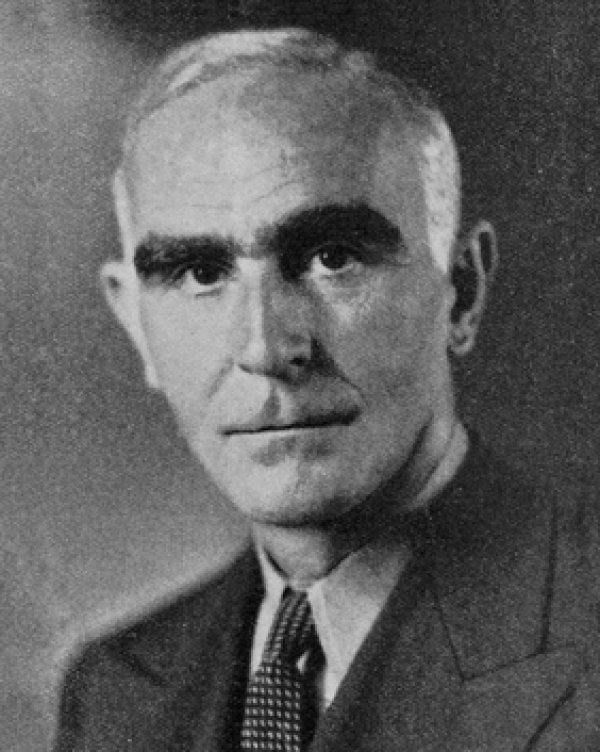

The London fog, thick as ever, clung to my coat as I stepped out of Tottenham Grammar. Little did I know, a world away from those cobbled streets, I'd be shaping the very course of a global conflict. My name is Arthur Blaikie Purvis, and though born in Britain, my life's work would unfold across the vast expanse of North America.

The London fog, thick as ever, clung to my coat as I stepped out of Tottenham Grammar. Little did I know, a world away from those cobbled streets, I'd be shaping the very course of a global conflict. My name is Arthur Blaikie Purvis, and though born in Britain, my life's work would unfold across the vast expanse of North America.

The Great War they called it then. I found myself immersed in the intricate dance of procuring explosives, a grim necessity. America, a land of burgeoning industry, became my proving ground.

Then, Canada beckoned. A new chapter, leading Canadian Industries Limited. William Lyon Mackenzie King, a man of quiet resolve, entrusted me with the daunting task of chairing the National Employment Commission in 1936. I learned the pulse of a nation, the strength and resilience of its people.

Then came the storm, the Second World War. The British government, facing the looming shadow of Nazi aggression, called upon me once more. I was appointed the Director-General of the British Purchasing Commission. What did it mean, I was the only man in Washington who could sign an order, write a cheque and secure arms for Britian without having to ask Westminster for permission.

A daunting title, but a crucial role. To secure the sinews of war from the United States, to arm our homeland against the darkness. Jean Monnet, a brilliant mind, and I formed the Anglo-French Purchasing Board, a fragile alliance against a common enemy.

It became obvious that France would fall, a tragedy unfolding, across the English Channel, almost before our eyes. The weight of responsibility pressed down. Those French contracts, millions of dollars worth of vital weaponry, hanging in the balance. I seized them. Brazenly, I marched into the Pentagon with my chequebook and demanded those armmaments for the British cause. I wrote the cheque for $612 million, and then hoped that Westminster would transfer the funds.

Then, the delicate dance of negotiations, a faction of Congress wanted to stay neutral and out of the war. Eventually I won them over with the Destroyers for Bases Agreement, securing torpedo boats, aircraft, and munitions, bartering with the very fabric of American neutrality.

In 1941, as Chairman of the British Supply Council in North America. My days were a whirlwind, a constant stream of meetings, negotiations, and strategic decisions. Henry Morgenthau Jr, as United States Secretary of the Treasury, one of the most important men in America.

He and I were kindred spirits, a man of unwavering resolve. Although representing different Governments, we worked as one, two ministers in a single cabinet, united by a common purpose.

I was appointed to the Privy Council (an advisor to the King), a recognition of my service, but fate had other plans.

At the last moment I was ordered to fly back to America and, on that fateful day in August, I boarded a Liberator to fly back to Washington. The take-off from RAF Heathfield was terrifying, the sudden, violent crash. My life, abruptly extinguished.

Churchill was distraught, he said my loss was grievous because I held so many threads together between Britian, Canada and America. Franklin Rosevelt said that he had lost a friend.

What about Morgenthau, with whom I had worked so closely, called me one of the rarest persons he had ever known and the ablest man in Washington

Purvis Hall, at McGill University in Canada, a quiet reminder of my legacy. But my true legacy lies in the countless lives saved, the tides of war turned, the unwavering dedication to a cause greater than myself. Though I never lived to be sworn into the Privy Council, my name, and my work, will forever be etched in the annals of history.

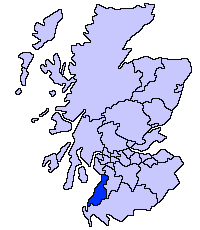

I lie in a grave looked after by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Ayr, I was only 51 when I died.

Hear the narrated story.